Abstract Link to heading

In a previous post, T5 the Old New Thing, we briefly touched upon CodeT5 and CodeT5+. Now, we aim to dive deeper into these topics.

I have previously explored CodeBERT and GraphCodeBERT. These models, based on BERT and RoBERTa architectures, excel at code understanding and retrieval tasks. However, they fall short when it comes to code generation tasks. It’s worth noting that these models share a common theme: they utilize unique pretraining objectives tailored specifically for source code.

CodeT5 Link to heading

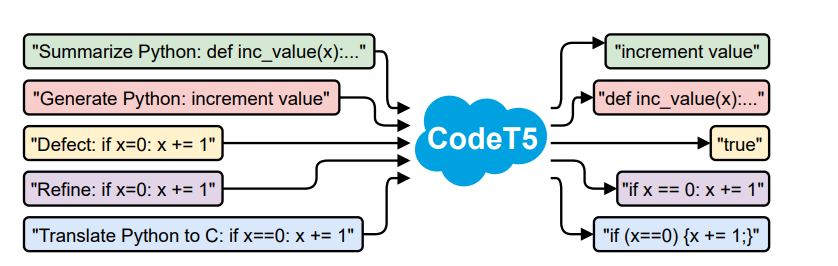

Introduced by Wang et al.(2021), CodeT5 aims to bridge the gap between Encoder-Only models like CodeBERT, which excel at code understanding but fall short at code generation, and Decoder-Only models like GPT, which are proficient at code generation but perform poorly at code understanding tasks. As a result, CodeT5 is a comprehensive Encoder-Decoder model, pretrained on a vast corpus of unimodal pure Source Code and bimodal Source Code and Natural Language pairs. It uses a variety of pretraining objectives, some of which are specifically designed for source code.

Intuition Link to heading

CodeT5’s implementation is based on the T5 model, a sequence-to-sequence model. Therefore, we formulate all our problems as sequence-to-sequence tasks.

By pretraining on a large corpus of code, we can leverage developer-assigned identifiers such as comments, variable types and their names, function names, signatures, return types, and many more. To capture the semantics of these identifiers, CodeT5 introduces an identifier-aware pretraining objective. This trains the model to distinguish which tokens are identifiers and how to recover them when they are masked. This is beneficial for code understanding and generation tasks, as it allows the model to learn the alignment between code and comments, and to recover identifiers when they are masked.

Tokenization Link to heading

The tokenization of the input sequence is performed using a custom-trained Byte Pair Encoding (BPE) tokenizer. This subword tokenizer splits words into subwords and is used to build a vocabulary of 32k tokens. We also introduce several special tokens ([PAD], [CLS], [SEP], [MASK0], [MASK1], … [MASK99]) to represent the input sequence. It’s worth noting that this differs from the original T5 model, which used a SentencePiece tokenizer. The reason is simple: our custom-trained BPE tokenizer performs better on source code, whereas the original T5 tokenizer was encoding common code tokens like [,],{,} as unknown tokens.

Input/Output representation Link to heading

The input representation of CodeT5 consists of a sequence of tokens, which is a concatenation of Natural Language (NL) and Programming Language (PL) tokens.

$$x = ([CLS], w_1, \cdots, w_n, [SEP], c_1, \cdots, c_m, [SEP]) $$

- $[CLS]$ is a special token placed at the beginning of the sequence. Similar to BERT, this token represents the entire sequence and can be used later for classification or retrieval tasks.

- $[SEP]$ is a special token that separates the NL and PL tokens

- $n$ represents the number of NL word tokens.

- $m$ represents the number of PL code tokens.

Abstract Syntax Tree (AST) Link to heading

To learn code-specific features, we utilize the AST of the source code. We extract node types for each node and introduce a sequence of binary labels $y {0,1}^m$ to represent whether a code segment $c_i$ is an identifier or not.

Pretraining Link to heading

For the corpus, we use the CodeSearchNet dataset and a collection of C/C# open-source Github repositories. The pretraining objectives we use are as follows:

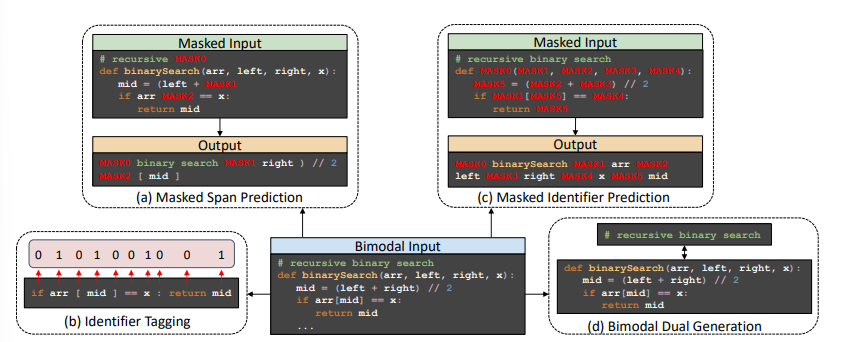

- Masked Span Prediction

- Identifier Tagging

- Masked Identifier Prediction

It’s worth noting that Identifier Tagging and Masked Identifier Prediction utilize information from the AST, which is the source of their power.

Masked Span Prediction (MSP) Link to heading

This well-known pretraining objective, employed by T5, involves corrupting a span of tokens and requiring the decoder to recover the original tokens, including sentinel tokens. The corruption rate is 15%, and the span length is sampled from Uniform(1,5). We employ whole word masking to avoid partial masking.

Loss Link to heading

$$ L_{MSP}(\theta) = \sum_{t=1}^k - \log P_{\theta}(x_t^{mask}| x^{\backslash mask}, x_{<t}^{mask})$$

- $x^{\backslash mask}$ represents the masked input

- $x^{mask}$ is the masked sentence that the decoder predicts

- $k$ is the number of tokens in $x^{mask}$

- $x^{mask}_{<t}$ is the span sequence generated so far

Identifier Tagging (IT) Link to heading

This pretraining objective trains the model to distinguish between identifiers and non-identifiers in the code, akin to syntax highlighting. This objective only activates the encoder and uses the contextual representation of the PL tokens right before they are passed to the decoder. We map these contextual representations to a sequence of probabilities. Unfortunately, the paper does not provide exact details on how this is done, nor does the source code. My assumption is that they add an additional projection layer with some sort of normalization (like L2). The output of the projection layer will be a single scalar that is then passed through a sigmoid function, yielding the probability that the token is an identifier.

Loss Link to heading

$$ L_{IT}(\theta_e) = - \sum_{i=1}^m y_i \log p_i + (1 - y_i) \log (1 - p_i)$$

- $\theta_e$ represents the encoder parameters

Again, the paper does not mention this, but I expect they may not even choose to send the output from the encoder to the decoder, as the decoder is not used in this task.

Masked Identifier Prediction (MIP) Link to heading

This pretraining objective can be viewed as a sort of de-obfuscation task and is based on the paper DOBF. The idea is that we mask specific identifiers in the code. The role of the decoder is then to produce the output key-value pairs, where the key is the masked identifier ([MASK0, MASK1, …]) and the value is the masked value.

Loss Link to heading

$$L_{MIP}(\theta) = \sum_{j=1}^{|I|} - \log P_{\theta}(I_j| x^{\backslash I}, I_{<j}) $$

- $x^{\backslash I}$ is the masked input

Bimodal Generation Link to heading

During pretraining, the decoder only observes masked identifiers. However, we want our model to generate code from Natural Language (NL) or generate NL from code. In this step, we feed NL into the encoder and expect the decoder to generate the Programming Language (PL), and vice versa. Since we anticipate handling multiple programming languages, we prepend the input with a special token representing the programming language (, , etc.) or natural language ().

Fine-Tuning Link to heading

We expect our model to handle the following tasks:

Code Summarization Link to heading

In this task, we expect an English summary of the code snippet. We evaluate the model on the BLEU-4 score, and it outperforms CodeBERT and PLBART, with the latter trained on a significantly larger dataset.

Code Generation Link to heading

We expect the model to generate code snippets from NL descriptions. We evaluate the model on CodeBLEU, which is more suitable for comparing code generation models as it takes into account language syntax, semantics, and structure. CodeT5 outperforms GPT-2 in this task.

Code Translation Link to heading

The task involves translating one programming language into another. We evaluate the model on Exact Match, and CodeT5 manages to generate functions that are more readable and maintain the same functionality as the original code. This indicates the model’s strong generalization capabilities. Here, the performance is better than that of GraphCodeBERT.

Code Refinement Link to heading

The task is to remove bugs. In this task, the performance is comparable to GraphCodeBERT, but it lags slightly behind.

Defect Detection Link to heading

The task is to detect if a code snippet is vulnerable or not. Performance-wise, we outperform all models, including GraphCodeBERT and PLBART, which were the state-of-the-art at the time the article was published.

Clonde Detection Link to heading

In this task, we measure the similarity of two code snippets, determining if they are the same or not. As with Defect Detection, CodeT5 achieved the current state-of-the-art score.

Remarks Link to heading

Performance-wise, we cannot really compare this model to current ones, because CodeT5 comes in two variants: Small (120M) and Base (220M). These sizes are dwarfed by the current 7B CodeLlama or even 22B CodeStral. Still CodeT5 is a strong model, and it serves as a base for many other models.

CodeT+ Link to heading

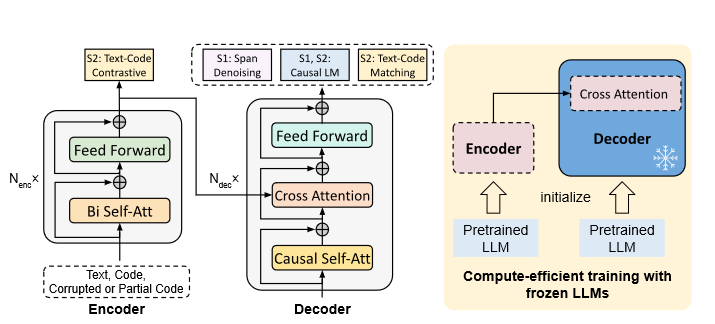

Let’s talk about CodeT5+ Wang et al. (2023). This model, developed by the same research team, builds upon CodeT5 and scales its size up to 16B parameters. A few points are worth mentioning. Firstly, the authors are leaning more towards Decoder-only models, leading them to adopt a shallow encoder and a deep decoder architecture (the Decoder has more attention stacks than the Encoder). Secondly, they note that pretraining a Language Model from scratch is expensive and time-consuming. To address this, they bootstrap the encoder and the decoder from existing models and connect them with a cross-attention layer at the last layer of the decoder. During pretraining, they freeze the decoder and train only the encoder and the cross-attention layers. Lastly, they introduce a couple of new pretraining objectives like Text-Code Contrastive Learning and Text-Code Matching. Let’s delve deeper into the model.

Model Link to heading

It’s not vastly different from the plain T5. Bootstrapping it from existing models is not unusual. What makes this model unique is its ability to work in different modes: encoder-only, decoder-only, or full encoder-decoder mode. Why is this important? Let’s imagine that we need the encoder’s embedding to perform a code similarity search; there’s no need to use the decoder for that. Similarly, if we need to perform code completion, this task can be accomplished by the decoder alone. Running it in full encoder-decoder mode can be extremely useful for a Retrieval Augmented Generation (RAG) task, where the encoder’s contextual representation is used for retrieval and the decoder is used for generation.

Bootstrapping Link to heading

For the decoder, the authors choose CodeGen-Mono 350m and for the Decoder CodeGen-Mono 2B, 6B and 16B.

Pretraining Link to heading

Given that CodeT5+ can operate in different modes, we have multiple stages of pretraining, each with different objectives and types of data (Uni-modal code only and Bi-modal code and natural language pairs).

1 Stage: Uni-modal Link to heading

In this stage, we leverage only code data. While the code may contain comments, we do not treat them as natural language-programming language pairs. The pretraining objectives are:

Span Denoising Objective Link to heading

This objective is similar to the Masked Span Prediction, where we randomly replace 15% of the tokens with [MASK] tokens in the encoder input, and we require the decoder to recover them by generating a combination of these spans. The difference is that we concatenate different code files into sequences and chunk them into fixed-length sequences. This task activates both the encoder and the decoder.

Causal Language Modeling Link to heading

This task is split into an encoder-decoder and a decoder-only task. Importantly, in both variants, we select a random pivot location, where all the tokens before the pivot are treated as the source sequence (context), and the tokens after the pivot are the target we aim to predict.

- Seq2Seq CausalLM variant: We prepend the source sequence with a special [CLM] token and feed it to the encoder. The rest of the sequence is the target for the decoder to generate. The pivot is somewhere between 10% and 90% of the sequence length.

- Extreme Seq2Seq CausalLM variant: We prepend the source sequence with a special [CLM] token and require the decoder to generate the entire sequence. In this case, we train the decoder to operate independently from the encoder.

2 Stage: Bi-modal Link to heading

In this stage, we have code-snippet and natural language pairs. This improves the alignment between code and natural language, enhancing cross-modal generation and understanding tasks. We have three pretraining objectives:

Text-Code Contrastive Learning Link to heading

This objective requires some patience to understand fully. The idea is that we want to learn representations of code such that code snippets that have similar functionality should have similar representations, and code snippets with different functionality should have different representations. The goal is to align the feature space of text and code representations by pulling together positive text-code pairs and pushing apart negative pairs. This objective only activates the encoder, which encodes a text or code snippet into a continuous representation. An [CLS] token is prepended to the input sequence and is used for the final embedding of the sequence. We pass the [CLS] representation through a linear layer and use L2 norm to map it to a 256-dimensional embedding.

Momentum Encoder Link to heading

We’ve already mentioned that we need positive and negative pairs. To get these, we use a Momentum Encoder (MoCo). Technically, this is just another encoder that is identical to the encoder we already use. The goal of this encoder is to generate our negative samples by maintaining a queue of embeddings of samples from previous mini-batches. When there are new samples, it enqueues them, and when the queue is full, it dequeues the oldest samples. The parameters of the momentum encoder are updated by linear interpolation of the original encoder and the momentum encoder, ensuring the consistency of the representations across training steps.

The goal of the momentum encoder is to have access to negative samples (samples from previous batches), and since it evolves slowly (slower than the original encoder), it improves the stability of the training process.

Remarks Link to heading

While I’m already familiar with negative sampling, typically, to construct the negative sample, we just took a random sample from the training dataset. Since the momentum encoder evolves slower than the original encoder, we force the embeddings to evolve slower as well, ensuring that the embeddings for the negative samples won’t drastically change from one batch to another. This is a clever trick to stabilize the training process.

Text-Code Matching Link to heading

Unlike Text-Code Contrastive Learning, which only activates the encoder, Text-Code Matching is a decoder-only objective.

The goal is for the decoder to learn to determine if two snippets share the same semantics, thereby better aligning the text and code modalities. We prepend a task-specific [Match] token to the code input sequence to inform the decoder of the text-code matching functionality and append an [EOS] token to the end of the code input. We take the [EOS] representation at the last decoder layer as the text-code cross-modal alignment representation. This representation is passed through a linear layer and used for binary matching tasks, predicting if the text-code pair is a match or not. To get the negatives, we employ a negative mining strategy.

Remarks Link to heading

Why is this a decoder-only task? It’s hard to answer since the paper does not provide an explanation. Naturally, this task would be a fit for our encoder, but since we already use the encoder in Text-Code Contrastive Learning, we can use the decoder for this task. This forces both to learn kind of the same thing, but capturing different aspects of the problem. Also, the authors argue that the model can be used in a decoder-only setting, and by forcing the decoder to learn this task, it can improve its performance in this setting.

Text-Code Causal LM Link to heading

This objective activates both the encoder and decoder and focuses on code-to-text and text-to-code generation. If the input is text, we prepend a [CDec] token to the input sequence to the decoder, forcing the decoder to operate in code generation mode. If the input is code, we prepend a [TDec] token to the input sequence to the decoder, forcing the decoder to operate in text generation mode. This type of causal LM closes the gap between pretraining and fine-tuning for generative downstream tasks.

Instruction Tuning Link to heading

Since this is a post-ChatGPT paper, we are also interested in giving our model the ability to follow instructions. For this, we pretrain it using the CodeAlcapa dataset, which is a dataset of code snippets and their corresponding instructions.

Performance Link to heading

Here, things get more complicated. The evaluation was on similar tasks as CodeT5, and in general, it exceeds the performance of CodeT5 when compared in equal settings (220M versions), and the improvements are significant. However, most comparisons were done to other Open Source Language Models like CodeBERT, GraphCodeBERT, PLBART, which are all smaller models. In pure code generation, CodeT5+ outperforms LLaMa and even StarCoder, thus making it the state-of-the-art model for code generation tasks. Unfortunately, the gap to proprietary models like ChatGPT is still large.

Remarks Link to heading

This whole bootstrapping from existing LLMs is nice, however, it makes a lot of comparisons more troublesome. I would really like to see some ablation studies on the different pretraining objectives and how they affect the model’s performance.

Remarks Link to heading

CodeT5+ offers a significant performance improvement over CodeT5. However, CodeT5 has seen wide adoption in the field of Cybersecurity and has been applied for Automated Vulnerability Repair. It also serves as the base for BinT5 and HexT5, which is not the case for CodeT5+ yet.

The lack of adoption of CodeT5+ may be due of its relative new age, or its permisive licencing for its 16B instruct version (Or maybe 16B is just too large).

One noteworthy aspect of CodeT5+ is its fine-tuning for the RaG task, which is a very interesting direction for future research.

Since I am not an native English speaker, I am using ChatGPT to improve my writing and fix my grammar mistakes you can read the Original here