Abstract Link to heading

This is not my first gig where I write about State Space Models. I already mentioned them here and here. Now what is the deal with this Mamba(2) thing? They are proving to be an alternative to the strong Transformer++ architecture (Transformer++ models like LLaMa are based on Rotary Embedding, SwiGLU, MLP, RMSNorm, without linear bias, sometimes with grouped query attention and/or sliding window attention). Hold on, if this Transformer++ models work well, why do we need altneratives? There are multiple reason:

Performance: Self-attention with a causal mask has a quadratic bottleneck, and as the sequence length becomes longer, this becomes a problem. Resolving this issue is a field of active research. One possible solution is to use Linear Attention, which we will cover since it is one of the basics Mamba-2 builds upon. Another possibility is to use Sliding Window Attention, which constrains the context for the next token generation to the past N tokens, where N is the window size. This alleviates the memory requirements, though it makes the model less capable. Technically speaking, State Space Models scale linearly in terms of sequence length (quadratically with the state size, but in general, this is fixed).

State: Attention is stateless; there is no hidden state that is sequentially updated. This is both a good and a bad thing. It is good because if the model needs to look something up, it will take into account everything it has seen before. This is super important as it enables in-context learning. It is bad because it has to keep track of everything it has seen before. With state space models, we have a hidden state that is updated every time we have a new input. Because of this, we can view the hidden state as a compressed representation of everything it has observed before. Again, this is both good and bad. It is good because this compressed representation is smaller than the whole sequence, making it more efficient. It is bad because the hidden state has to be large enough to store everything that is important and at the same time remain relatively small to be efficient, AND (it is capitalized for a reason!) the mechanism that updates the state has to do it in a meaningful way (this is something we are going to explore in more detail).

Alternatives: I get it, this is subjective, but if we only do research into Transformers, we may never find anything better.

Before we dive into the details of Mamba-1 and Mamba-2, let me give you a brief summary:

Mamba-1: The idea behind Mamba is to make the updating mechanics of its hidden state input-dependent. This may sound intuitive, but previous SSM variants like H3 were Linear Time Invariant, which means that their updating mechanism did not change with time. I the remainder of the post I will use the term Mamba and Mamba-1 interchangeably.

Mamba-2: Mamba-2 is generally just a simplification of Mamba, with stronger constraints on the structure of the hidden space update matrix and moving some projections to the beginning of the layer. This enables the usage of common scaling strategies used in transformers, like tensor and sequence parallelism, and the ability to split input sequences across multiple GPUs. Also, the authors build a solid theoretical foundation behind SSMs and Semi-Separable Matrices and prove they have a primal-dual relationship with Linear Attention.

Mamba Link to heading

Structured State Space Models (S4) Link to heading

Structured State Space model is defined as a one-dimensional function of sequences $x(t) \in R \rightarrow y(t) \in R$ mapped trough a hidden state $h(t) \in R^N$.

The actual model consist of four parameters $\Delta, A, B, C$ and we can express it as:

$$h(t) = Ah(t) + Bx(t) $$ $$y(t) = Ch(t)$$

- $A \in R^{N \times N}$ is contained to be diagonal

- $B \in R^{N \times 1}$

- $C \in R^{1 \times N}$

Because of the constraints, we can represent all matrices with N numbers. To generalize to a multi-dimensional input, we apply the SSM independently to each channel, making the total memory requirements $O(BLDN)$.

Since we work with continuous time but process discrete data, we need to discretize the model:

$$ h_t = \bar{A} h_{t-1} + \bar{B}x_t $$ $$ y_t = Ch_t $$

- $\bar{A} = f_A(\Delta, A)$

- $\bar{B} = f_B(\Delta, A, B)$

- with $f_A, f_B$ being discretization rules. For example we can use Zero-Order hold

To actually compute this model, we use global convolution:

$$ y = x * \bar{K} $$

- K is our kernel that is implicitly parametrized by an SSM

$$ \bar{K} = (C\bar{B}, C\bar{AB}, \cdots, C\bar{A}^k\bar{C}, \cdots)$$

The benefit of this is that we can use Fast Fourier Transform to compute the convolution in $O(N \log N)$ time.

Linear Time Invariance (LTI) Link to heading

Just from the definition above, we can see that the $(\Delta, A, B, C)$ do not depend on $x$ nor $t$. This is one of the main drawbacks and the reason why State Space Models were struggling with in-context learning.

Selective State Space Models (S6) Link to heading

One easy fix is to take the same model as above but make the parameters $\Delta, A, B$ functions of the input:

Algorithm Link to heading

- we have input $x: (B,L,D)$ (Batch, Length, Dimension)

- output $y: (B, L, D)$

- $A: (D,N) \leftarrow \text{Parameters}$

- $B: (B,L,D) \leftarrow s_B(x)$

- $C: (B,L,D) \leftarrow s_C(x)$

- $\Delta: (B,L,N) \leftarrow \tau_{\Delta}(\text{Parameter} + s_{\Delta}(x))$

- $\bar{A}, \bar{B}: (B, L, D, N) \leftarrow \text{discretize}(A,B)$ 6: $y \leftarrow \text{SSM}(\bar{A}, \bar{B}, C)(x)$

- $A$ is still diagonal

- $s_B(x) = \text{Linear}_N(x)$

- $s_C(x) = \text{Linear}_N(x)$

- $s_{\Delta} = \text{Broadcast}_D(\text{Linear}_1(x))$ (we choose this due to a connection to Recurrent Neural Networks)

- $\tau_{\Delta} = \text{softplus}$ (we choose this due to a connection to Recurrent Neural Networks)

- $\text{Linear}_d$ is parametrized projection to dimension d

Selective Scan Link to heading

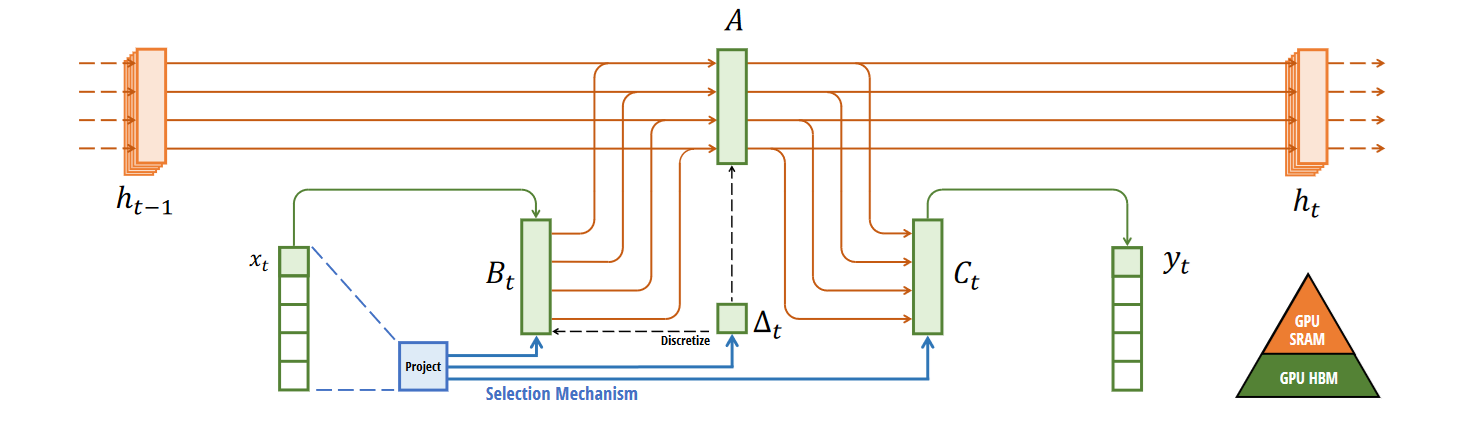

Since the dynamics of the model are dynamic, we cannot use global convolution anymore. Because of this, we define selective scan, which is a hardware-aware algorithm. The actual implementation is rather involved. The main idea is that we load the parameters $\Delta, A, B, C$ from HBM to SRAM, perform the discretization and recurrence in SRAM, and write the final output of size (B, L, D) back to main memory (HBM). To reduce memory requirements, the intermediate steps are not stored but recomputed during the backward pass.

Benefits of (Natural) Selection Link to heading

Because of the selection mechanism, the model can choose what to store (or not) in its hidden state based on what it currently sees. It may also choose to reset its hidden state and start over. Selection enables the model to have strong in-context learning capabilities.

Mamba Layer Link to heading

The core of the Mamba architecture is the Mamba layer:

We are already familiar what is happening inside the SSM (Selective Scan) part of the Mamba. Prior to it we have two projections that expand the dimensionality of the input, than we perform short convolution as in M2 Bert with torch.nn.Conv1d on one branch on the other branch we apply just SiLu non-linearity (This is the same as the Gated approach found in other LLMs). After that we perform an additional projection, and we have all the inputs prepared for the SSM block. The output of the SSM block is than multiplied with the residual gate branch and finally we project the dimension back to match the input dimension.

Mamba-2 Link to heading

Mamba is a cool innovation, and it has led to multiple cool models, especially attention-SSM hybrid models like Samba and Zamba. However, the authors recognize some of its shortcomings. Its biggest weak point compared to Transformers is the lack of research in terms of scaling. For Transformers, we have multiple system optimizations on how to split up a model or how to split up processing long sequences into more GPUs. Here is two of them:

- Tensor Parallelism: This allows splitting each layer in a large Transformer model onto multiple GPUs on the same node.

- Sequence Parallelism: This allows splitting a sequence into smaller parts, with each GPU holding one part.

Mamba-2 is designed in a way that allows for Sequence Parallelism by passing the recurrent state between multiple GPUs. Tensor Parallelism is possible because of independent parallel projections of A, B, C, and X inputs of its SSM part.

Semi-Separable Matrices Link to heading

This is a special structured matrix. We say that a lower triangular matrix $M$ is N-semi separable if every submatrix contained in the lower triangular part has rank at most N.

Here, we are more interested in a special representation of N-semi separable called Sequentially Semi Separable (SSS).

Sequentially Semi Separable (N-SSS) Link to heading

A lower triangular matrix $M \in R^{(T,T)}$ has an N-sequentially semiseparable representation if we can write it as:

$$ M_{ij} = C_j^TA_j \cdots A_{i+1}B_i$$

- $B_0, \cdots, B_{T - 1}, C_0, \cdots, C_{T-1} \in R^N$ are vectors

- $A_0, \cdots, A_{T-1} \in R^{(N,N)} $

To express it in matrix form we define the SSS operator:

$$ M = SSS(A_{0:T}, B_{0:T}, C_{0:T})$$

It turns out that every N-semiseparable matrix M is also an N-sequentially semiseparable matrix. The main const of N-SSS representation that we can compress down the parameters to $O(NT)$

State Space Duality Link to heading

Let’s start by exploring a special case of 1-semiseparable (1-SS or just 1SS). This can be written in the Sequentially Semi-Separable form as:

$$SSS(a,b,c) = \text{diag}(c) \cdot M \cdot \text{diag}(b) $$

- $M_{ij} = \prod_{t=j}^i a_t = a_{j:i}^{\times}$

M is an 1-SS

$$M = 1SS(a_{0:T}) = \begin{bmatrix} 1 \\ a_1 && 1 \\ a_{2}a_1 && a_2 && 1 \\ \vdots && \vdots && \ddots && \ddots \\ a_{T-1}\cdots a_1 && a_{T-1}a_2 && \cdots && a_{T-1} && 1 \end{bmatrix}$$

State Space Models are Separable Matrices Link to heading

We make a special assumption that we have a State Space Model without projections (no B, C) and the state dimension $N = 1$. Then we can express the multiplication $y = Mx$ as a recurrence:

$$y_t = a_{t:0}x_0 + \cdots + a_{t:t}x_t $$ $$y_t = a_t(a_{t-1:0}x_0 \cdots a_{t-1:t-1}x_{t-1} + a_{t:t}x_t $$ $$y_t = a_t y_{t-1} + x_t$$

We can generalize this further by expressing any State Space Model as matrix multiplication by an N-semiseparable matrix in a sequentially semiseparable form:

$$y = SSM(A,B,C)(x) = SSS(A,B,C) \cdot x $$

Linear(Recurrent) and Dual(Quadratic) form Link to heading

We already know we can express a State Space model as a matrix multiplication by an N-separable matrix in a sequentially semiseparable form:

$$ y = SSS(A,B,C) \cdot x $$

However, if we naively first compute the $SSS$ part and then multiply by $x$, we end up with an $O(T^2)$ complexity. There is a more efficient recurrent way. However, let’s break down the quadratic form first, since it has a tight connection to Attention.

Dual (Quadratic) Form Link to heading

Here, we take a small detour from SSMs and look into Linear Attention. We can express the attention mechanism as:

$$Y = \text{softmax}(QK^T) V $$

This is the most common form of attention, called Softmax Attention. By applying a causal mask, we get the following:

$$Y = (L \circ \text{softmax}(QK^T)) \cdot V $$

- $L$ is an lower triangular matrix with ones on and below the main diagonal

In linear attention we drop the softmax to get:

$$Y = (L \circ (QK^T)) \cdot V $$

This form is way nicer and we can rewrite it using einsum as:

$$Y = \text{einsum}(TN,SN,SP, TS \rightarrow TP)(Q,K,V,L)$$

Or we can express it as pairwise matrix multiplication:

- $G = \text{einsum}(TN,SN \rightarrow TS)(Q,K)$ resulting shape (T,S)

- $M = \text{einsum}(TS,TS \rightarrow TS)(G,L)$ resulting shape (T,S)

- $Y = \text{einsum}(TS,SP \rightarrow TP)(M,V)$ resulting shape (T,P)

- T, S are the target source dimensions, for autoregressive self-attention they are the same

- P is the head dimensionality

Linear (Recurrent) Form Link to heading

Until now, we have just removed the softmax operation. However, we can go further by changing the order of matrix association, resulting in the following:

$$(QK^T)V = Q(K^TV) $$

With this, we can re-express the definition of $Y$ as:

$$ Y = Q \cdot \text{cumsum}(K^TV)$$

- cumsum is just the cumulative sum

It may seem that we got rid of the causal mask. This is technically not true, since the cumsum operation is a causal operation, and we just hid it. To make this clearer, we can express the same equation using einsum:

- $Z = \text{einsum}(SP,SN \rightarrow SPN)(V,K)$ resulting shape (S,P,N)

- $H = \text{einsum}(TS,SPN \rightarrow TPN)(V,K)$ resulting shape (T,P,N) this being optimized with subquadratic matrix multiplication

- $Y = \text{einsum}(TN,TPN \rightarrow TP)(V,K)$ resulting shape (T,P)

Lets break down the equation:

- Expands the dimensionality by a factor N

- Uses the mask matrix L explicitly, we flatten the dimensions of (P,N) resulting in multiplying an lower triangular matrix with an vector. This just just an cumulative sum operation:

$$ y = \begin{bmatrix} 1 \\ \cdots && \ddots \\ 1 && \cdots && 1 \end{bmatrix}x \Leftrightarrow \begin{matrix} y_0 = x_0 \\ y_t = y_{t-1} + x_t\end{matrix} $$

- Contracts the dimensionality back to P

State Space Models and Recurrent Linear Attention Link to heading

The hints that there should be a connection between the recurrent form of Linear Attention and the State Space Model should be obvious.

Lets remind us about the definition of the State Space Model using SSS:

$$ Y = SSS(A,B,C) \cdot x $$

The SSS matrix M is defined as:

- $M_{ji} = C_j^TA_{j:i}B_i$

By constraining the A matrix to be diagonal $A = aI$ we can rearrange the terms a bit to get:

$$ M_{ji} = A_{j:i} \cdot (C_j^TB_i)$$

The equation for M in matrix form becomes:

$$L = 1SS(a)$$ $$M = L \circ (CB^T)$$

- $B,C \in R^{(T,N)}$

Now we can compute $Y = MX$ using einsum as:

- $G = \text{einsum}(TN,SN \rightarrow TS)(C,B)$ resulting shape (T,S)

- $M = \text{einsum}(TS,TS \rightarrow TS)(G,L)$ resulting shape (T,S)

- $Y = \text{einsum}(TS,SP \rightarrow TP)(M,X)$ resulting shape (T,P)

If we assume that S = T, we end up with the same equations as in the Recurrent form of Linear Attention. And that is it, we have our duality.

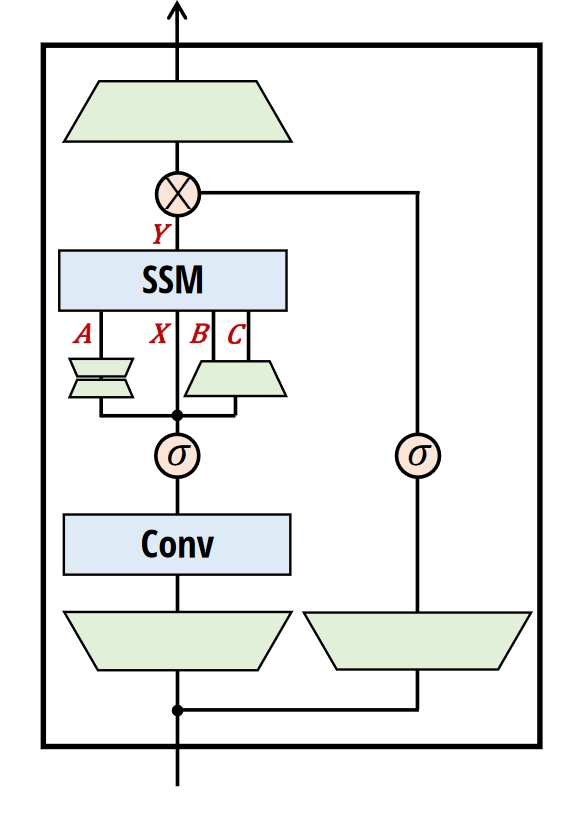

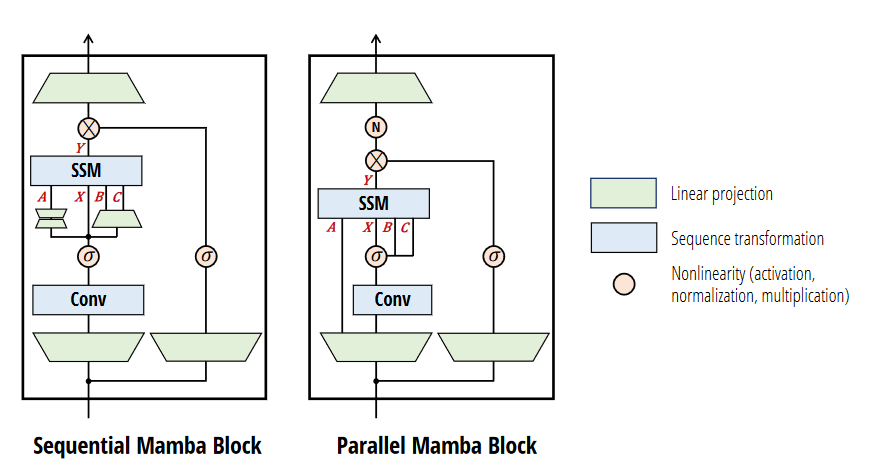

Mamba-2 Layer Link to heading

At the beginning, I mentioned that there are few differences between Mamba and Mamba-2. One of them is a stronger constraint on the matrix A, for Mamba-2 it is $A = aI$ in Mamba it was $A = \text{diag}(a)$. The reason to constrain to $A = aI$ is that we can express the SSM as a matrix multiplication of an 1-SS matrix, which is more efficient to compute.

In the image above, we can see the differences between Mamba and Mamba-2. While the idea of Mamba was to have a function $X \rightarrow Y$, in Mamba-2, we instead think of a mapping of $A, B, C, X \rightarrow Y$. Because of this, we can parallelize the computation of the projections at the beginning of the block. This enables tensor parallelism and reduces the number of parameters. This is also analogous to Attention, where $X, B, C$ correspond to $Q, K, V$.

Additionally, Mamba-2 introduces a larger head dimension $P$. While Mamba leverages $P =1 $, Mamba-2 leverages $P = {64, 128}$. Again, this is similar to conventions in Transformer Architecture. What does this head dimension in Mamba mean? If we have a head dimension of 1, we are computing an SSM for each channel independently. By increasing the head dimension, we achieve a sort of weight-tying where we share SSMs across multiple channels.

Overall, it may seem that Mamba-2 is less expressive than Mamba. However, due to optimizations, we are able to train Mamba-2 models with much larger state dimensions (in Mamba-1 we had $N=16$, whereas in Mamba-2 we can go up to $N=256$ or more), while also being much faster during training.

The model also adds an additional normalization layer, which improves the stability of larger models. There is nothing more to say about Mamba-2; it is simply a more efficient version of Mamba, incorporating many lessons learned from Transformers and the strong theoretical foundation behind SSMs and Semi-Separable Matrices.

Algorithm Link to heading

As with Mamba-1, we cannot use Global Convolution. For Mamba-2, we need an efficient way to compute the matrix $M$. Luckily, the computation is much simpler than for Mamba-1, and we do not need to implement a low-level GPU kernel. The algorithm consists mostly of matrix multiplications.

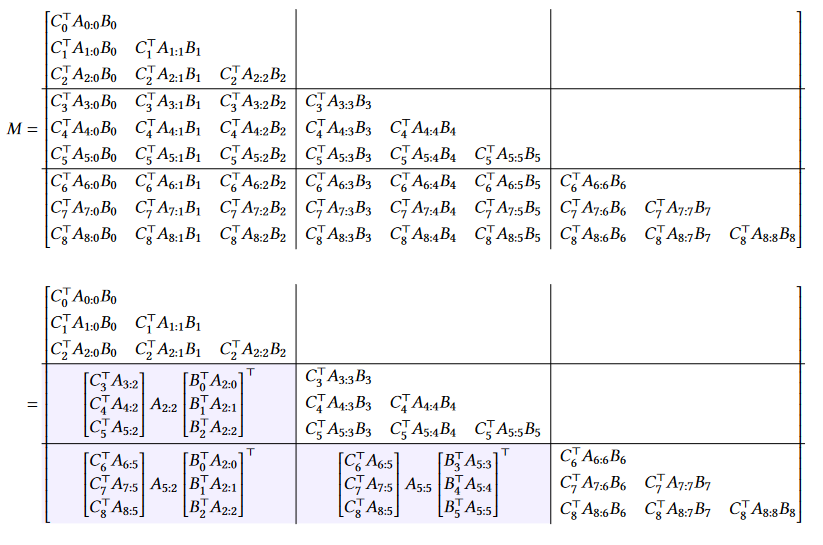

This is an example for $T=9$ where we decompose it into chunks of length $Q = 3$, we can generalize it as:

- $M^{(j,j)} = SSM(A_{jQ:(j+1)Q},B_{jQ(j+1)Q},C_{jQ:(j+1)Q}$ for the diagonal blocks

- $M^{(i,j)} = \begin{bmatrix}C_{jQ}^TA_{jQ:jQ-1} \ \vdots \ C^T_{(j+1)Q-1}A_{(j+1)Q-1:jQ-1}\end{bmatrix}A_{jQ-1:(i+1)Q-1} \begin{bmatrix}B_{iQ}^TA_{(i+1)Q-1:iQ} \ \vdots \ B_{(i+1)Q-1}^T A_{(i+1)Q-1:(i+1)Q-1}\end{bmatrix}^T$ for the off-diagonal low rank blocks

Diagonal Blocks Link to heading

The general idea is that $Q$ is rather small. Because of this, we can use the dual quadratic form of Structured Masked Attention (more on this later) and perform the computation for each block in parallel.

Low Rank Blocks Link to heading

Here, we have three parts (the following example is the breakdown of the leftmost bottom block from the image above):

- $\begin{bmatrix} C_6^T A_{6:5} \\ C_7^TA_{7:5} \\ C_8^TA_{8:5} \end{bmatrix}^T$ this are the left factors (C-block factors)

- $A_{5:2}$ this are the center factors (A-block factors)

- $\begin{bmatrix} B_0^T A_{2:0} \\ B_1^TA_{2:1} \\ B_2^TA_{2:2} \end{bmatrix}^T$ this are the right factors (B-block factors)

Pytorch Link to heading

Compared to Mamba-1’s selective scan the implementation is way more straight forward:

def segsum(x):

"""Naive segment sum calculation. exp(segsum(A)) produces a 1-SS matrix,

which is equivalent to a scalar SSM."""

T = x.size(-1)

x_cumsum = torch.cumsum(x, dim=-1)

x_segsum = x_cumsum[..., :, None] - x_cumsum[..., None, :]

mask = torch.tril(torch.ones(T, T, device=x.device, dtype=bool), diagonal=0)

x_segsum = x_segsum.masked_fill(~mask, -torch.inf)

return x_segsum

def ssd(X, A, B, C, block_len=64, initial_states=None):

"""

Arguments:

X: (batch, length, n_heads, d_head)

A: (batch, length, n_heads)

B: (batch, length, n_heads, d_state)

C: (batch, length, n_heads, d_state)

Return:

Y: (batch, length, n_heads, d_head)

"""

assert X.dtype == A.dtype == B.dtype == C.dtype

assert X.shape[1] % block_len == 0

# Rearrange into blocks/chunks

X, A, B, C = [rearrange(x, "b (c l) ... -> b c l ...", l=block_len) for x in (X, A, B, C)]

A = rearrange(A, "b c l h -> b h c l")

A_cumsum = torch.cumsum(A, dim=-1)

# 1. Compute the output for each intra-chunk (diagonal blocks)

L = torch.exp(segsum(A))

Y_diag = torch.einsum("bclhn,bcshn,bhcls,bcshp->bclhp", C, B, L, X)

# 2. Compute the state for each intra-chunk

# (right term of low-rank factorization of off-diagonal blocks; B terms)

decay_states = torch.exp((A_cumsum[:, :, :, -1:] - A_cumsum))

states = torch.einsum("bclhn,bhcl,bclhp->bchpn", B, decay_states, X)

# 3. Compute the inter-chunk SSM recurrence; produces correct SSM states at chunk boundaries

# (middle term of factorization of off-diag blocks; A terms)

if initial_states is None:

initial_states = torch.zeros_like(states[:, :1])

states = torch.cat([initial_states, states], dim=1)

decay_chunk = torch.exp(segsum(F.pad(A_cumsum[:, :, :, -1], (1, 0))))

new_states = torch.einsum("bhzc,bchpn->bzhpn", decay_chunk, states)

states, final_state = new_states[:, :-1], new_states[:, -1]

# 4. Compute state -> output conversion per chunk

# (left term of low-rank factorization of off-diagonal blocks; C terms)

state_decay_out = torch.exp(A_cumsum)

Y_off = torch.einsum('bclhn,bchpn,bhcl->bclhp', C, states, state_decay_out)

# Add output of intra-chunk and inter-chunk terms (diagonal and off-diagonal blocks)

Y = rearrange(Y_diag+Y_off, "b c l h p -> b (c l) h p")

return Y, final_state

Performance Link to heading

Mamba-2, like Mamba-1, with hidden state size ( N ), has the same training speed ( O(TN^2) ) and inference speed ( O(N^2) ). However, the biggest improvement is the use of matrix multiplication in Mamba-2, which is much more efficient than the selective scan in Mamba-1.

State Space Duality Additional Notes Link to heading

Overall, the State Space Duality paper introduces many concepts; here are arguably the most important ones:

Structured Masked Attention Link to heading

This builds upon the notion of linear attention, where we expressed the causal mask matrix L as a cumulative sum. However, we can generalize the mask matrix L to any matrix that supports fast matrix multiplication.

![[/images/structured_attention.png]]

In this case, we view the attention mechanism through the following equations (this is also the quadratic form mentioned earlier):

$$Y = MV$$

$$M = QK^T \circ L$$

Where L is our mask matrix, which we can choose as we like. In the context of State Space duality, we choose it as 1-semiseparable matrix.

Multi patterns for SSMs Link to heading

Again, this builds upon analogies to Attention, where multihead attention involves applying self-attention multiple times and concatenating the results. We can achieve something similar by applying the SSD algorithm and broadcasting it across multiple dimensions.

Multi-Contract SSM Link to heading

This is analogous to Multi-Query Attention, where we share K and V across all the heads of Q. For attention, this makes a lot of sense since we cache K and V pairs.

In SSMs, this is equivalent to sharing X and B across multiple heads of the SSM, and having C (parameters that control the contraction) be independent per head.

Multi-Expand SSM Link to heading

Here, we share C and X across multiple heads, and B (controls expansion) is independent per head.

Multi-Input SSM Link to heading

Here, we share B and C across multiple heads, and X is independent. For an SSM like Mamba, we consider X as the input. Because of this, it is a better fit to have a unique X per head.

Technically, we can view the S6 layer introduced in Mamba as having Head Dimension P = 1, which means that each channel has independent SSM dynamics A, and it is a Multi-Input SSM where we share B and C matrices across all channels.

TLDR; Link to heading

This was probably a lot to take in, so to sum it up, we introduced Mamba. Mamba is a State Space model whose dynamics are dependent on the input, which improves its ability for In-Context learning. Because we want efficient computation, we need to derive a hardware-efficient algorithm, and to do that, we need to enforce structure on the matrices used by Mamba. Mamba-2 tackles the efficiency problem by enforcing even more constraints, making the model more contained but easier to scale and allowing for larger hidden dimensions.