Abstract Link to heading

Till now we have considered only learning the Value or Q function and estimating the policy from those. In the next few posts, we are going to look into directly learning the policy. Why directly learn the policy? First, Q learning has a lot of issues involving the Deadly Triad; second, if we have continuous actions we cannot really use it; and lastly, Q learning always learns a deterministic policy, and in cases of partially observed stochastic environments (which is nearly always what we have), having a stochastic policy is proven to be better.

Policy Gradient Link to heading

I teased a bit, yes we are going to use (stochastic) Gradient Descent to optimize (this is also known as policy search) the following loss:

$$ J(\pi) \triangleq E_{\pi} [ \sum_{t=0}^{\infty} \gamma^t R_{t+1} ]$$ $$ = \sum_{t=0}^{\infty} \gamma^t \sum_s \left( \sum_{s_0} p_0(s_0) p^{\pi}(s_0 \rightarrow s, t) \right) \sum_a \pi(a|s) R(s, a)$$ $$ = \sum_s \left( \sum_{s_0} \sum_{t=0}^{\infty} \gamma^t p_0(s_0) p^{\pi}(s_0 \rightarrow s, t) \right) \sum_a \pi(a|s) R(s, a)$$ $$ = \sum_s \rho^{\gamma}_{\pi}(s) \sum_a \pi(a|s) R(s, a)$$

- $\rho_{\pi}^{\gamma}(s) \triangleq \sum_{t=0}^{\infty} \gamma^t \sum_{s_0} p_0(s_0) p^{\pi}(s_0 \rightarrow s, t)$ this measures the time spent in non-terminal states

- it is NOT a probability measure, since it is not normalised but can be normalized by exploiting $\sum_{i=0}^{\infty} \gamma^t = \frac{1}{1 - \gamma}$ if $\gamma < 1$ this yields

- $p_{\pi}^{\gamma}(s) = (1 - \gamma) \rho_{\pi}^{\gamma}(s) = (1 - \gamma) \sum_{t=0}^{\infty} \gamma^t p_t(s)$

- it is NOT a probability measure, since it is not normalised but can be normalized by exploiting $\sum_{i=0}^{\infty} \gamma^t = \frac{1}{1 - \gamma}$ if $\gamma < 1$ this yields

- $p_t^{\pi}(s) = \sum_{s_0} p_0(s_0) p^{\pi}(s_0 \rightarrow s, t)$ this is the marginal probability of being in state $s$ at time $t$

- $p^{\pi}(s_0 \rightarrow s, t)$ is the probability of going from $s_0$ to $s$ in $t$ steps

We abuse the notation a bit by treating $\rho$ as a probability measure we get: $$ E_{\rho_{\pi}^{\gamma}(s)}[f(s)] = \sum_{s} \rho_{\pi}^{\gamma}(s) f(s)$$

And our final loss is: $$ J(\pi) = E_{\rho_{\pi}^{\gamma}(s), \pi(a|s)}[R(s, a)]$$

Theorem Link to heading

Now we differentiate the loss to get:

$$ \nabla_{\theta} J(\theta) = \sum_{s} \rho_{\pi}^{\gamma}(s) \sum_{a} Q^{\pi}(s, a) \nabla_{\theta} \pi_{\theta}(a|s)$$ $$ = \sum_{s} \rho_{\pi}^{\gamma}(s) \sum_{a} Q^{\pi_{\theta}}(s, a) \pi_{\theta}(a|s) \nabla_{\theta} \log \pi_{\theta}(a|s)$$ $$ = E_{\rho_{\pi}^{\gamma}(s) \pi_{\theta}(a|s)}[Q^{\pi_{\theta}}(s, a) \nabla_{\theta} \log \pi_{\theta}(a|s)]$$

- $\nabla_{\theta} \log \pi_{\theta}(a|s)]$ this is also known as the score function and it is totally unrelated to the score function in Denoising Diffusion, which is the gradient with respect to a log probability: $ \nabla_{\theta} \log \pi_{\theta}(a|s) $

Since it is a gradient, we can follow it to regions with higher reward! Now you can also see that the equation contains the Q function! Even in policy-based methods, we frequently use the Value, Q, or Advantage function (difference between the Value and Q function) since they stabilize the loss.

Reinforce Link to heading

So naive policy gradient is said to have high variance! This is because we do a Monte Carlo rollout of the policy, which has low bias but, as said, high variance. To reduce the variance we need to introduce a baseline function, let’s look at the equations:

$$ \nabla_{\theta} J(\pi_{\theta}) = \sum_{t=0}^{\infty} \gamma^t E_{p_t(s) \pi_{\theta}(a_t|s_t)} [\nabla_{\theta} \log \pi_{\theta}(a_t|s_t) Q_{\pi_{\theta}}(s_t, a_t)]$$

$$ \approx \sum_{t=0}^{T-1} \gamma^t G_t \nabla_{\theta} \log \pi_{\theta}(a_t|s_t)$$

- $G_t \triangleq r_t + \gamma r_{t+1} + \gamma^2 r_{t+2} + \dots + \gamma^{T-t-1} r_{T-1} = \sum_{k=0}^{T-t-1} \gamma^k r_{t+k} = \sum_{j=t}^{T-1} \gamma^{j-t} r_j$ this is the reward-to-go and is estimated using Markov Chain rollout of the policy, hence the high variance part

As mentioned before, we introduce a baseline function $b(s)$:

$$\nabla_{\theta} J(\pi_{\theta}) = E_{\rho_{\theta}(s) \pi_{\theta}(a|s)} [\nabla_{\theta} \log \pi_{\theta}(a|s) (Q_{\pi_{\theta}}(s, a) - b(s))] $$

Baseline Functions Link to heading

It can be anything, it has just one requirement:

$$ E[\nabla_{\theta}b(s)] = 0$$

A common choice is either the Value Function $b(s) = V_{\pi_{\theta}}(s)$ or Advantage Function $b(s) = Q_{\pi_{\theta}}(a, s)$

Estimator Link to heading

Thus our update for the parameters $\theta$ becomes:

$$\theta \leftarrow \theta + \eta \sum_{t=0}^{T-1} \gamma^t (G_t - b(s_t)) \nabla_{\theta} \log \pi_{\theta}(a_t|s_t)$$

The update has an intuitive explanation:

We compute the sum of discounted future reward induced by a trajectory, compared to a baseline and if it is positive we increase $\theta$ to make this trajectory more likely otherwise we decrease $\theta$, or in simpler terms we reinforce good behavior and penalize bad.

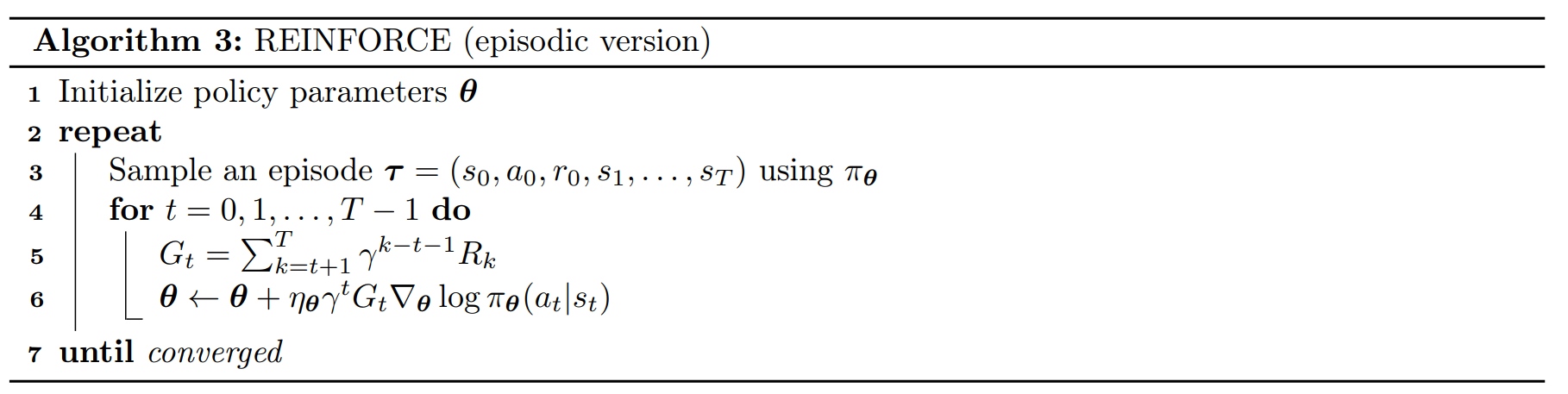

Algorithm Link to heading

Final Remarks Link to heading

This is the basis of Policy-Based Reinforcement Learning. In the next posts, we will look into an alternative approach called Actor-Critic methods, where instead of MC policy rollout we use Temporal Difference to estimate $G_t$. However, as it turns out, neither Reinforce nor Actor-Critic methods guarantee monotonic improvement in the learned policy, and we turn to Policy Improvement methods which contain the currently popular Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO) method known from Large Language Models!