Abstract Link to heading

Last time we looked into the weak points of State Space Models (Mamba, Mamba2), especially when compared with Attention-Based models (LLama, GPT-like). They lack in terms of in-context learning. To alleviate this, we focused on SSM-Transformer Hybrids and introduced multiple models that do this differently. Here we look into the expressivity of State Space Models from two formal perspectives. The first is from the perspective of Circuit complexity and later from the perspective of Formal Languages.

We cover the following two papers:

- The Expressive Capacity of State Space Models: A Formal Language Perspective

- The Illusion of State in State-Space Models

TLDR Link to heading

SSMs and Transformers have similar strengths and weaknesses; however, there is complementary synergy, giving a more theoretical reason for hybrid architectures.

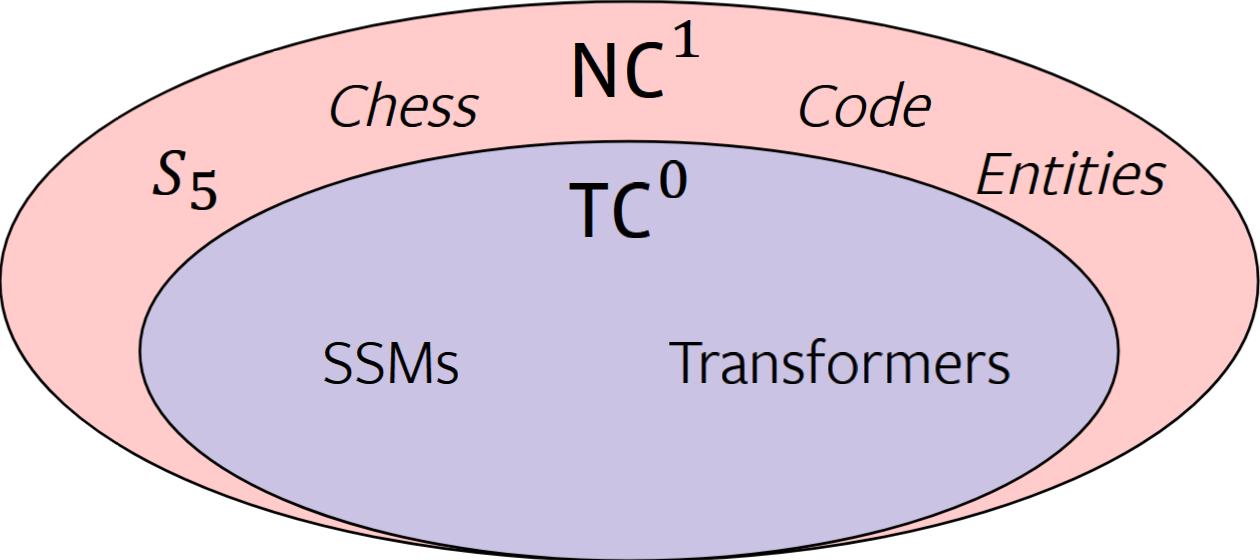

Circuit Complexity Link to heading

Circuit complexity is a branch of computational complexity. We can view a circuit as a computational graph in Neural Networks, where each node is an operation with edges between nodes that are connected. In this article, there are two important classes of circuit complexity, $TC^0$ and $NC^1$.

$TC^0$ Link to heading

These are circuits that have bounded (constant) depth, we have no limit on the number of inputs (unbounded fan-in) and we can only use AND, OR and Threshold gates (the output of this gate is 1 if the sum of inputs exceeds a threshold, otherwise it is 0). The last constraint is that the size of the circuit is polynomial in the input length. The importance of this class is that problems that lie in this class can be extremely parallelized.

Example Link to heading

The canonical example is Integer multiplication. Following a divide-and-conquer style approach, we can take a sequence of integers, split them into smaller subsequences, multiply the subsequences to get intermediate results (this can be done in parallel) and finally multiply the intermediate values together. If we assume that we can at most multiply 2 integers at a time, we can compute the result in $\log_2 (n)$ steps.

Nick’s Class 1 ($NC^1$) Link to heading

The depth of the circuit has a logarithmic bound ($O(\log n)$), we have a fixed (bounded fan-in) number of inputs, and we can only use AND and OR gates. The last constraint is that the size of the circuit is polynomial in the input length. This class represents problems that are sequential in nature and are hard to parallelize.

Example Link to heading

Here I introduce a couple of examples to make things more explicit:

- Evaluating boolean formulas: you have a bunch of boolean values with AND and OR between them, and sometimes grouped into groups. Technically this is to some degree parallelizable, since we can evaluate subgroups independently, but there may be dependencies that need to be evaluated first.

- Regular expressions: for those who do not know, regular expressions are compiled down to state machines, and you need to process character by character. Again if you have unions you may process different parts in parallel but otherwise you are forced to move one character at a time.

- Simulating finite automata: everything that is processed by finite state machines, where the state depends on the input, is determined by the order in which we receive the input. Altering this order can result in vastly different states.

SSMs, Transformers, and RNNs Link to heading

Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) are sequential by nature and can solve problems in $NC^1$. However, this sequential nature makes them hard to parallelize, and mainstream research started to favor Transformers, which allow for extreme parallelization. However, Transformers are stuck in $TC^0$ and cannot express strictly sequential problems. Mamba technically can emulate a Recurrent Neural Network, but this is only theoretical since it requires an infinite number of layers. Because of this, Mamba is stuck in $TC^0$.

Is $TC^0$ enough? Link to heading

To answer this, I’ll give a couple of problems that lie beyond $TC^0$:

- Tracking chess moves

- Evaluating code

- Tracking entities in a narrative

- Evaluating graph connectivity

- Solving linear equations

“Hey, but ChatGPT, Claude, and Llama are good at generating code!” That is true, but reasoning about what the result will be given some inputs is beyond their capabilities. They can emulate the reasoning, but they are bound to make mistakes.

Expressive power of SSMs Link to heading

There are two decision choices that bottleneck the expressivity of an SSM-like model.

Linearity of the hidden state $$h_i = \bar{A}h_{i-1} + \bar{B} x_i$$ The new state $h_i$ is just a linear combination of the previous hidden state and the input. We can increase the expressivity by introducing nonlinearity: $$h_i = \text{sign}(\bar{A}h_{i-1} + \bar{B} x_i)$$ However, this makes it less obvious how to parallelize the computation.

Input Independence of Transition Matrix A A does not really depend on $x$; in Mamba, A is diagonal and in Mamba2 it is just a scalar. If we introduce dependency between $x$ and $A$ we get a more expressive SSM; this has already been done in the LiquidSSM paper. By introducing either of these two changes, we can teach the model to track chess pieces.

Empirical Results Link to heading

Even though neither SSMs nor Transformers are equipped for state tracking, they are capable of emulating this behavior. Overall, Mamba has an edge over Transformers in this emulation. The main reason is that Mamba is at least theoretically capable of emulating RNNs, whereas Transformers are not.

Formal Language Perspective Link to heading

In formal languages, our input is always a string, and we have grammars that define how we can process this string. There are 3 basic building blocks that we can use to build these grammars:

- Finite state automata (we already know this is $NC^1$)

- Counters

- Stacks

A canonical example is Regular Expressions; as mentioned before, processing Regular Expressions is done by a State Machine. This state machine then has counters and can use a stack to keep track of previously seen characters.

Context-free, Context-sensitive Link to heading

There are two types of grammars:

- Context-free: this is where most programming languages fall into, and they are good grammars. For example, if you have a programming language that has a for keyword, this keyword has a single meaning independently of the context where it is used. You probably saw different types of for loops, but they do the same thing, that is iterating through something that is iterable.

- Context-sensitive: this is natural language, and it is way less nice. You may have words that have different meanings depending on how they are used. Let’s imagine a state machine that is processing a context-sensitive grammar, and it encounters a word. Now depending on previous words, this can have a vastly different meaning, and in the extreme case, it may require keeping track of the whole previously seen text just to interpret the current word (or looking into the future).

Problems Link to heading

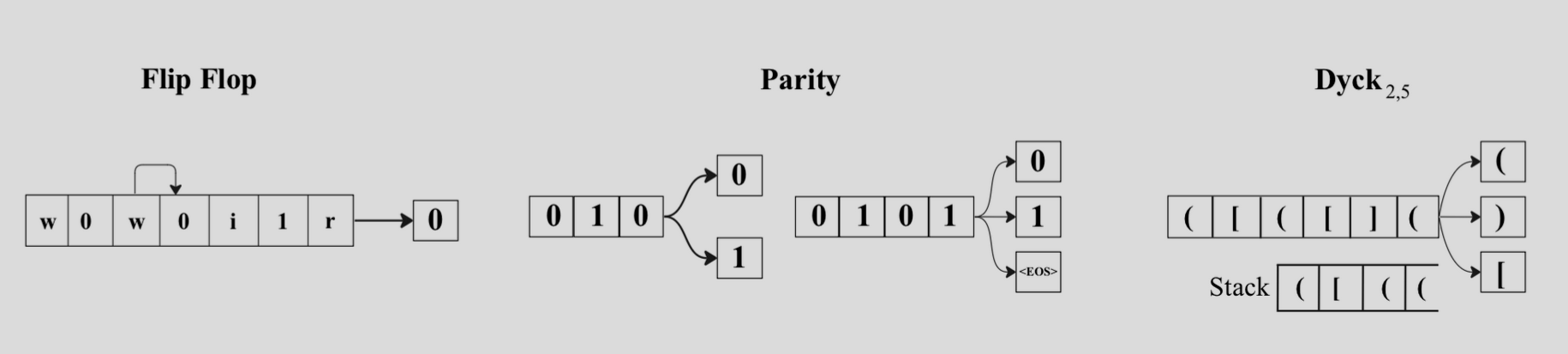

To study the strengths and weaknesses of SSMs and Transformers, we first introduce 3 sample problems; these sample problems emulate string processing showcasing the different weaknesses and strengths of transformers.

Flip-Flop Link to heading

The Flip-Flop problem is defined as a sequence of instructions and data. There are 3 instructions: Read, Write, Ignore. Each time we encounter a Write instruction, we store information into memory (this information is either 0 or 1); this information will be recalled by the next Read instruction.

This seems like a simple problem, but it serves as an abstraction for long-range reasoning. Recurrent Neural Networks like LSTM do a pretty good job; however, Transformers are struggling. The main pain point for Transformers to precisely attend to the last Write is that they would require strong positional dependence in the attention weights and also Transformers do not generalize well to arbitrary lengths since they require explicit positional encoding. In contrast, SSMs are able to model this problem to arbitrary lengths by employing two SSM layers.

Parity Link to heading

In Parity, we are given a bit string, which is just a string that can consist only of 0 and 1, and we require that there is an even number of 1s. If we look at it from the perspective of a State Machine, we can encounter the End Of String (EOS) character only if we have read an even number of 1s.

As before, RNNs can easily handle Parity; with Transformers, this is way more tricky, theoretically possible but empirically hard. For SSMs, it is similarly possible to Transformers; for example, Mamba is input dependent which is one requirement for SSMs to handle Parity, but its transition matrix A is non-negative, which makes this problem very hard, making Parity a problem that neither Transformers nor Mamba find easy to model.

Star-free Regular Languages Link to heading

For simplicity, we can view Regular Languages as the same thing as Regular Expressions, and by Star-Free we require them to not involve the Kleene Star *. There is a special conjecture where we can re-express any Star-Free regular language as a Flip-Flop like state tracking, where we recall information that we previously observed.

Transformers are theoretically equipped to model Star-Free languages, but they fail to do so since it requires unique hard attention, which is hard to construct.

Here are two examples of Star-Free problems: Unbounded counting and Hierarchical Structures.

Unbounded Counting Link to heading

The simplest is the Dyck-1 language, and it can be viewed as matching open and closed brackets. Let’s define the following string “(())”, it has two open and two closed brackets. This problem can be modeled using a counter which increments by one if it observes “(” and decrements by one for “)”. We can formally define Dyck-1 as $a^nb^n$, where in our case $a=(, b = )$; what is important about Dyck-1 is that it is a basic example of a context-free grammar.

A more complex example is a Shuffle-Dyck-k language, which is a shuffle of multiple Dyck-1; this is defined as $a^nb^nc^n$. Here we require two counters, one for tracking $a^nb^n$ and $b^nc^n$. What is important here is that this is an example of a context-sensitive grammar!

As it turns out, this problem can be well modeled using SSMs, showcasing that SSMs can model context-free and context-sensitive grammars as well.

Hierarchical Structures Link to heading

Again we are using bracket matching; let’s start with a couple of examples: “([()]), (()[]), (([])[])”, we can already see that there is a hierarchical structure. Formally these are bounded-depth Dyck $\text{Dyck}_{K,h}$. According to Chomsky-Schutzenberger, if we push the depth $h \rightarrow \infty$ we have the fundamental backbone of context-free languages.

Again this is a problem that is a breeze for RNNs. A Two-layer Transformer is doing exceptionally well, but this is mainly due to the positional encoding. Similarly to Transformers, two layers of SSM can model the problem well, where the first layer is responsible for encoding the depth of the brackets and the second layer tracks the last open bracket for each level of depth.

Modulo Counting Link to heading

Modulo counting is just counting the number of matching entries and taking the modulo of this count. This falls within Star-Free Languages, but SSMs fail to model this problem.

Results Link to heading

Transformers and SSMs are bounded to solve the same class of problems; however, they have different strengths. Transformers showcase better selective copying behavior, and SSMs are better at Flip-Flop-like state tracking. The biggest limiting factor for SSMs is their non-negativity of hidden state evolution, which allows for better scaling but reduces their expressivity. Overall, even though there is the word “State” in State Space Models, in Mamba this state is not comparable to the state found in Recurrent Neural Networks, but Mamba is managing to “fake” the state to a certain degree.