Abstract Link to heading

For a while now I have a new passion and that is binary reverse engineering and vulnerability exploitation. This interest has led me to create CodeBreakers a platform dedicated to applying machine learning to reverse engineering, vulnerability detection, exploitation, and other cybersecurity-related applications.

I found two notable research papers where T5 has been applied to reverse engineering are BinT5 and HexT5. Before we dive deep into the details of these papers, let’s first explore the basics of reverse engineering.

Reverse Engineering Link to heading

To understand reverse engineering, we must first understand compilation. Compilation is the process of translating a high-level programming language, such as C (yes, C is considered a high-level programming language), into machine code. Machine code is a format that your CPU can directly execute. The actual execution of machine code is a bit more complex, as an instruction like “add” can be further broken down into micro-code instructions. Instructions can be executed out of order, and with speculative execution, things can quickly become complicated, leaving room for errors and security vulnerabilities.

To keep things simple let’s continue with machine code. Machine code is essentially a sequence of bytes. These bytes can represent instructions or data (the concept of “code is data, data is code” is a fundamental idea of Von Neumann’s architecture). These bytes can, without loss of generality, be reconstructed back into assembly code. Assembly code is a human-readable representation of machine code. However, it’s important to note that being human-readable does not necessarily mean it is easy to understand.

To give you an example of the following simple_main.c code:

#include <stdio.h>

int main(int argc, char const *argv[])

{

if (argc > 1) {

printf("More than one argument");

}

printf("Hello, World!\n");

return 0;

}

Compiled with GCC 11.4.0

gcc simple_main.c -o simple_main.so -no-pie -fno-stack-protector

Please never ever enable those 2 flags above in production code, i just want to keep the assembly as simple as possible.

We get this, it ain’t pretty, and it might contain more information than we asked for. However, it remains manageable, and in a reasonable timeframe, even an less experienced reverse engineer can extract the corresponding assembly for our main function::

0000000000401156 <main>:

401156: f3 0f 1e fa endbr64

40115a: 55 push rbp

40115b: 48 89 e5 mov rbp,rsp

40115e: 48 83 ec 10 sub rsp,0x10

401162: 89 7d fc mov DWORD PTR [rbp-0x4],edi

401165: 48 89 75 f0 mov QWORD PTR [rbp-0x10],rsi

401169: 83 7d fc 01 cmp DWORD PTR [rbp-0x4],0x1

40116d: 7e 14 jle 401183 <main+0x2d>

40116f: 48 8d 05 8e 0e 00 00 lea rax,[rip+0xe8e] # 402004 <_IO_stdin_used+0x4>

401176: 48 89 c7 mov rdi,rax

401179: b8 00 00 00 00 mov eax,0x0

40117e: e8 dd fe ff ff call 401060 <printf@plt>

401183: 48 8d 05 91 0e 00 00 lea rax,[rip+0xe91] # 40201b <_IO_stdin_used+0x1b>

40118a: 48 89 c7 mov rdi,rax

40118d: e8 be fe ff ff call 401050 <puts@plt>

401192: b8 00 00 00 00 mov eax,0x0

401197: c9 leave

401198: c3 ret

The first column represents the memory address where the instruction is stored, the second column contains the opcodes, and the third column provides a human-readable representation of the opcode, supplemented with some comments. In the actual code, we observe some function calls, memory manipulation, and conditional jumps. Anyone with a basic understanding of calling conventions and assembly could reasonably comprehend what’s happening.

Let’s dive deeper and invoke the strip command to obtain this beauty. Stripping significantly complicates matters as there is no main function at all. Fortunately, we have access to the unstripped version (and we added the -no-pie flag to GCC), so our main function remains at 0x401156. However, a pattern emerges: stripping the binary results in the loss of substantial information, such as function symbols and their boundaries. Most commercial software is stripped, and it’s safe to assume that most malware is stripped as well.

I hope I’ve managed to convince you that reverse engineering is challenging in its own right, and stripping binaries only amplifies this difficulty. When we introduce various source code obfuscations, we find ourselves facing a task that is nearly impossible.

BinT5 Link to heading

Builds upon CodeT5 Base (220m) and fine-tunes it to perform reverse engineering, specifically to generate natural language summaries for binary functions. Why summaries? It’s important to remember that compilation is not a one-to-one function, making the recovery of actual source code an impossible task. However, providing a high-level overview of a function’s behavior gives the reverse engineer a good starting point, indicating where to focus and what to expect.

Input Data Link to heading

The authors note the absence of a reference dataset for reverse engineering tasks, leading them to create their own dataset. Named Capybara, it contains 214k decompiled C binaries for projects built for Ubuntu using Travis CI, compiled with GCC using the following optimization flags: -O0, -O1, -O2, -O3. These binaries are then stripped. One of the significant downsides of C projects is the lack of a standard single documentation format. To address this, the authors apply various heuristics to provide documentation for the functions.

The actual input of the model is not the assembly code, but the decompiled pseudo C code. The authors use Ghidra to generate pseudo C code. The choice of pseudo C over assembly is due to its greater readability and superior performance in experiments. Since CodeT5 was pretrained on C source code, and there is a substantial similarity between C source code and pseudo C code (it’s referred to as pseudo C code because it doesn’t have to be compilable), making it safe to assume that it will work well.

Demistriped Functions Link to heading

By leveraging Ghidra, we can lift assembly code to pseudo C code. However, in stripped binaries, functions can be inlined, or CALL instructions can be replaced by JUMP instructions. The actual recovery of function boundaries is a separate research topic. Due to these imperfections, the authors introduce demistriped functions. These are functions lifted from binaries that are not stripped using strip command, but the identifiers like function names or variable names are manually removed.

Remarks Link to heading

This scenario seems highly unrealistic, potentially limiting its applicability in real-world situations.

Performance Link to heading

The authors compare BinT5 to GraphCodeBERT and PolyGlotCodeBERT, both fine-tuned on the Capybara dataset. On the BLEU-4 metric, BinT5 scores 3 to 5 points higher than the aforementioned models.

However, the model significantly struggles with stripped binaries. This struggle stems partly from inherent flaws in the decompilation process, particularly with inlined functions where the decompiler cannot recover the function boundaries.

In the case of demi-striped functions, the model performs significantly better. However, this is not a real-world scenario, which limits the model’s usefulness.

Ablevation Link to heading

Duplicates Link to heading

The Capybara dataset contains some level of duplicates, which is natural since different projects tend to rely on shared libraries. By removing duplicates (or near duplicates) from the dataset, the model loses a lot of its performance on Exact Match. However, based on human evaluation, the summaries remain reasonable.

Source Code Comments vs Function Names Link to heading

From a performance perspective, having comments in the code seems less important than actual identifiers, with function names contributing the most. However, in stripped binaries, we do not have function names.

Data Leakage Link to heading

There are a few concerns about data leakage from CodeT5. CodeT5 was pretrained on a dataset containing C/C# code. Unfortunately, the dataset is not public, making it difficult to assess if the foundational model was pretrained on source code that is similar (or the same) as that used in BinT5. The authors claim that the data leakage is minimal since the performance of the model is comparable to fine-tuned GraphCodeBERT and PolyGlotCodeBERT (which were not pretrained on any C code) on the Capybara dataset.

Remarks to BinT5 Link to heading

I would like to applaud BinT5 as it represents the first attempt to apply T5 (or an LLM) to the reverse engineering of stripped binaries. However, the results are not particularly promising. The model performs well, but only in a very specific scenario (demi-striped), which is unlikely to occur in the real world.

In my personal opinion, the authors missed the main point of T5. They did not introduce any new pretraining objectives that would help the model better understand the binary code. Fortunately, we have HexT5 as an alternative.

HexT5 Link to heading

HexT5 picks up where BinT5 left off, introducing several pretraining objectives designed to enhance the model’s understanding of binary code. The authors recognize that existing reverse engineering methods tend to focus narrowly on single tasks such as function name recovery, variable name recovery, binary code summarization, or binary function similarity detection. With HexT5, the authors aim to tackle all these tasks simultaneously, asserting that models trained on multiple objectives tend to outperform those trained on a single task. Additionally, they work with binaries compiled for different architectures (x86, x86_64, arm32, arm64), different compiler flags (-O0, -O1, -O2, -O3), and four compilers: clang-7.0, clang-9.0, gcc-7.2.0, gcc-8.3.0.

Like BinT5, HexT5 builds on top of T5 Base (220m).

Input Data Link to heading

As with BinT5, HexT5 doesn’t directly leverage binary code (assembly), but first decompiles it to pseudo C. However, in this case, Hex-Rays is used instead of Ghidra. Hex-Rays is a commercial (and expensive) product with performance that is arguably superior to Ghidra.

The source for the binaries is GNU Binutils, and the data is partitioned in a cross-project or cross-binary manner.

- Cross Project: A binary, for example,

lsorcat, will be located in either the training or test set, including all the functions from that binary, compiled with different compiler flags, different compilers, and different architectures. - Cross Binary: This approach splits each binary into a set of functions, with each function being in either the training or test set. If a function is in the training set, then all its versions (compiled with different compiler flags, different compilers, and different architectures) are in the training set as well.

Remarks Link to heading

Cross Project partitioning mirrors real-world scenarios, as it’s unlikely that a reverse engineer will have access to some parts of the binary but not others. However, this is somewhat misleading, as binaries often share libraries and third-party code. Unfortunately, Cross Project partitioning performs worse than Cross Binary partitioning.

DWARF Link to heading

The authors utilize DWARF, a debugging format used to map binary code to source code, as a bridge between the two. They extract symbols from the DWARF information and map them to the decompiled pseudo C code using their addresses. This allows for the recovery of variable names, function names, and other identifiers. However, in stripped binaries, the biggest challenge remains the detection of function boundaries. Unfortunately , this paper does not address this issue, limiting the model’s usefulness in real-world scenarios.

Normalization Link to heading

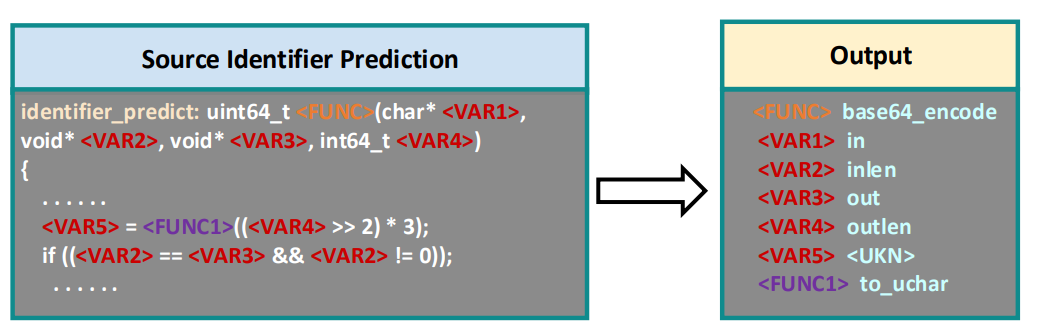

In stripped binaries, variable and function names often lack meaning. To address this, we replace them with special tokens. For variables, we use tokens “<VAR>, <VAR2>, …, <VAR100>”. For the functions we want to reverse engineer, we reserve the token “<FUNC>”. For all functions called from within, we use “<FUNC1>, <FUNC2>, …, <FUNC50>”. Comments inside pseudo code, generated by the decompiler, bear no meaning and are therefore deleted. There is one edge case: variables that lack any meaningful name. In this case, we replace these variables with “<UKN>” instead of “<VAR…>”.

Pretraining Objectives Link to heading

Before we explore the pretraining objectives, let’s revisit the model’s goal. We want it to recover variable names, function names, summarize binary code, and detect binary code similarity. All these tasks can be viewed as a function that takes a programming language (in our case, pseudo C) and produces natural language, with binary code similarity detection being slightly different.

Why is this important? Most current LLMs aim to provide a conversational agent-like experience. HexT5 does not attempt to do this, eliminating the need for a Natural Language to Programming Language alignment objective. While this inability to prompt the model makes it more constrained, it allows the model to focus more on the task at hand.

HexT5’s core consists of four pretraining objectives: Masked Span Prediction, Source Identifier Prediction, Bimodal Single Generation, and Contrastive Learning.

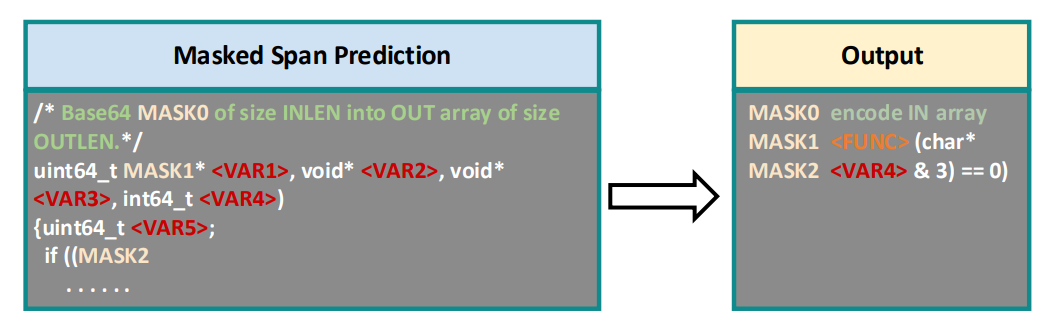

Masked Span Prediction Link to heading

This is essentially the same as in CodeT5. We take chunks of the input, mask them, and expect the model to recover the masked tokens. This objective aids in aligning pseudo code and comments.

Source Identifier Prediction (SIP) Link to heading

This objective, inspired by DOBF, aims to teach the model deobfuscation. This means we attempt to recover the obfuscated variable names and function names. In our case, we try to predict the values hidden behind “<FUNC>, <FUNC..>” and “<VAR>” tokens.

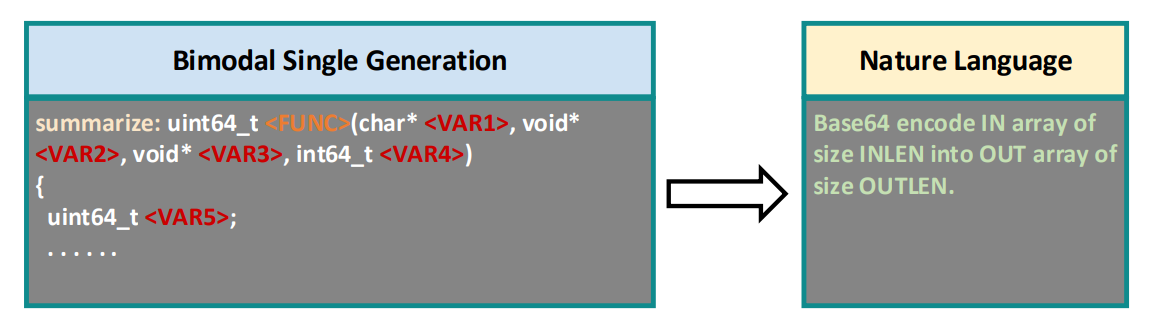

Bimodal Single Generation Link to heading

Goal of the objective is to align the programming language to natural language generation. Here we feed the whole Pseudo C code to the model and we want it to generate a natural language summary of the code. From the models perspective this objective is the same as SIP, to distinguish between the two objectives the authors add a hard prompt token “summarize” before the Pseudo C code (for SIP the prompt token is “identifier_prediction”).

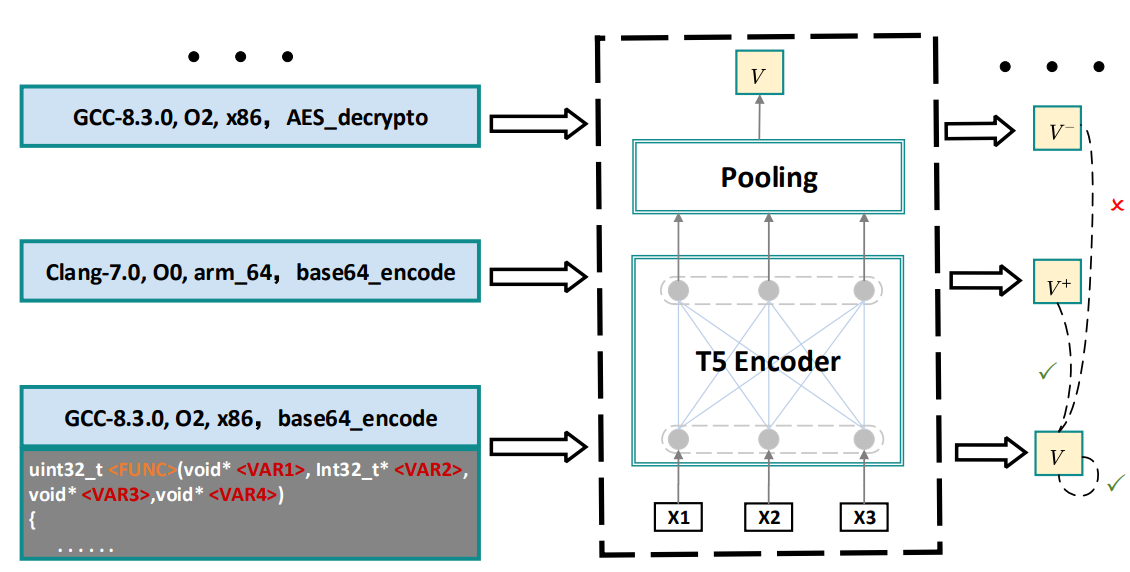

Contrastive Learning Link to heading

The concept behind contrastive learning is to bring the contextual representations of similar functions closer together and push the representations of dissimilar functions further apart. We’ve already seen this in CodeT5+. However, in the case of HexT5, we don’t employ a Momentum Encoder. Instead, we use the remaining samples from a given mini-batch as negative samples, and for the positive samples, we use the same function but compiled with different compiler flags, different compilers, and/or different architectures.

One thing not explicitly stated in the paper is whether, if a given function is selected to be in a mini-batch, all the versions of that function are also in the mini-batch. I expect that this is the case.

Contrastive Learning is a sequence-level objective. This means we take a Pseudo C code snippet, pass it through the encoder part of the model, which yields a contextual representation for each token. To actually get the embedding, we average these contextual representations. We take this representation and pass it into the contrastive learning objective:

$$ L_{CL} = -\log \frac{e^{sim}(V,V^+)/\tau}{\sum_{j\in B} e^{sim (V,V_j^-)/\tau}} $$

- $sim$ is the similarity function, in our case cosine similarity

- $V^+$ are the positive samples

- $V^{-}$ are the negative samples, there is an additional way to sample the negatives, we can apply an random dropout mas to V_j, however I find this approach more confusing

Performance Link to heading

To cut a long story short, HexT5 has set the state-of-the-art in Binary Code Summarization, Variable Name Recovery, Function Name Recovery, and Binary Code Similarity Search. Interestingly, in Binary Code Summarization, they also benchmarked it against Gepetto. Gepetto is an Ida-Pro plugin that leverages OpenAI’s Chat-GPT to generate summaries for binary functions.

Remarks Link to heading

Function Boundaries Link to heading

Both models have some obvious downsides. The detection of function boundaries is a significant problem and without a solution, the models are not particularly useful in real-world scenarios.

Data Leakage Link to heading

In my personal opinion, data leakage is a serious concern. Let’s consider a paper from Shang et. al 2024, a newer study applying LLMs like GPT-4 and CodeLlama 7B for reverse engineering. They state that these autoregressive causal models perform much better than BinT5 or HexT5 (for HexT5, the reported scores are vastly different between the papers). These large causal foundational models have the capacity to memorize the training data, and since the training data is not public (for CodeLlama, we know it was pretrained on an additional 500B tokens or 864GB of source code, GPT-4 is unknown but due to Github Copilot’s Codex, we can assume it saw an incredible amount of source code, not just open source).

It is hard limit the amount of data leakage, especially if we use Pseudo C code, which may be in many cases be very similar to the original source code. Because of this I would like to see and focus my personal research on techniques that either work with the binary code directly or they choose a different intermediate representation that is not so similar to the original source code.

Disclaimer Link to heading

Since I am not an english native speaker, I use ChatGPT to help me with the text (Formatting, Spelling, etc). However I did write every single word in this blog post, If you are interested you can check the the original text here